Information boards at the Holocaust Victims Memorial Site – English version

TABLE 1 – before Holocaust

Jews have been present in the Sącz region since the Middle Ages. The first mention of their presence appears in the documents of the Kraków Jewish community in 1469, where Abraham of Sącz was listed. In the royal town of Nowy Sącz itself, Jews were allowed to settle from the 17th century onwards. King Michał Korybut Wiśniowiecki allowed Jews to settle within the city walls in 1673, after numerous fires and epidemics had swept through the town.

The newcomers settled mainly in the area around the castle; this is how the Jewish quarter gradually emerged. This is where the Germans would delineate the ghetto area during World War II. In the 18th century, thanks to the development of trade, the town became an increasingly attractive place to live. In 1740, more adherents of Judaism than Catholics lived in Nowy Sącz. There were two synagogues and a cheder (or a Jewish school). A cemetery was also established behind the city walls.

In the 19th century, Jews accounted for almost half of the town’s population, while in 1910, one in three inhabitants of Nowy Sącz was a follower of Judaism. Such proportions continued until the outbreak of World War II.

From 1830, the Jewish community of Nowy Sącz was ruled by the Halberstam family, who represented the Hasidic movement within Jewish orthodoxy. Its Nowy Sącz leader region was the great tzaddik (or pious, righteous) Rabbi Chaim Halberstam, famous as a miracle-worker and sage. He was known for helping those in need, regardless of their religion. He also got on well with representatives of other religions, especially with the Nowy Sącz Catholic parish priest, Jan Machaczek, as well as with the Lutheran pastor. Crowds of pious Jews would flock to Rabbi Halberstam’s grave on the anniversary of his death (April 1876).

Jews were full citizens in the Second Polish Republic. Jewish town councillors worked in the municipal government of Nowy Sącz. Jewish intellectuals, including doctors and lawyers, were part of the local elite. The town had Jewish reading rooms, libraries, theatres and even a revue troupe. Many Jews studied at university, earned degrees and took up academic posts. The largest part of the Jewish population earned their living through trade. Some businesses played a significant role in the region’s economy.

Of the rich mosaic of various political movements, Zionism became increasingly popular among Jewish youth. It advocated the establishment a Jewish state in Palestine.

Social care and charity had a strong tradition among the Jews of Sącz. A hospital on Kraszewskiego Street was an important institution in this regard.

Jews also actively participated in sports life. The most famous Jewish athlete was the football player Samuel Kippel – a pre-war star of the Sandecja sport club.

The outbreak of World War II and the German occupation brought a dramatic end to the world of the Nowy Sącz Jewish community.

TABLE 2 – Ghetto in the Piekło neighbourhood

The Germans created the ghetto in Nowy Sącz in August 1940. They divided it into two parts, separating Jews fit for work from those who could not work, the former group being located in the Piekło district – along Lwowska Street. The Piekło ghetto boundaries were marked by the Kamienica River, Paderewskiego Street to the east, and Zdrojowa and Głowackiego Streets to the north. The Jews placed there hoped that their usefulness to the Germans would guarantee them a better chance of surviving the war.

The so-called Judenrat (or Jewish Council), established by the Germans, had its headquarters at 17 Lwowska Street. Its aim was to implement the occupier’s orders effectively, for instance collect tributes imposed on the Jewish community. Those members of the Judenrat who initially tried to resist those orders were deported by the Germans to concentration camps, which effectively terrorised the others.

In 1940, the Germans allowed the reopening of the Jewish hospital on Kraszewskiego Street. Its staff provided medical help to the ghetto population. Despite the wartime limitations, a huge number of treatments were performed there. Doctors also made home visits. During the liquidation of the ghetto, the Germans murdered both the hospital staff and all the patients.

At 27 Lwowska Street there was a pharmacy run by the Polish pharmacist Albin Burz. He provided selfless help to all inhabitants of the ghetto. Numerous testimonies mention his heroic attitude.

The Union of Jewish Craftsmen was located at 25 Poprzeczna Street (today Sikorskiego Street).

The Germans carried out their crimes in the Piekło neighbourhood even before the final liquidation of the ghetto. Heinrich Hamann, the head of the Nowy Sącz Gestapo was a ruthless torturer. Mechel Fisz recalled that in June 1942, Hamann checked whether all Jews in the ghetto were employed. „He then found that my mother Chana Fisz wasn’t employed anywhere and ordered her to move to the other ghetto. I asked him to let her stay with me, but Hamann refused and shot her in the flat before my eyes.” On Gwardia Street, Gestapo men shot 35 people, including Salomon Goldberger, before his daughters’ very eyes. In July 1942, the German criminals Johan and Stuber murdered Rachela Federgrün for carrying two chickens for her children’s lunch. A month later, the president of the Judenrat, Baruch Berliner, was shot dead on Lwowska Street for no reason at all.

In August 1942, the Germans carried out a selection in front of the school on Kochanowskiego Street. They separated people fit for work, according to their own criteria, from a majority of Jews, the latter of whom were subsequently sent to the Belzec death camp.

Photo: Lwowska Street during WWII. The first building on the left housed the Judenrat

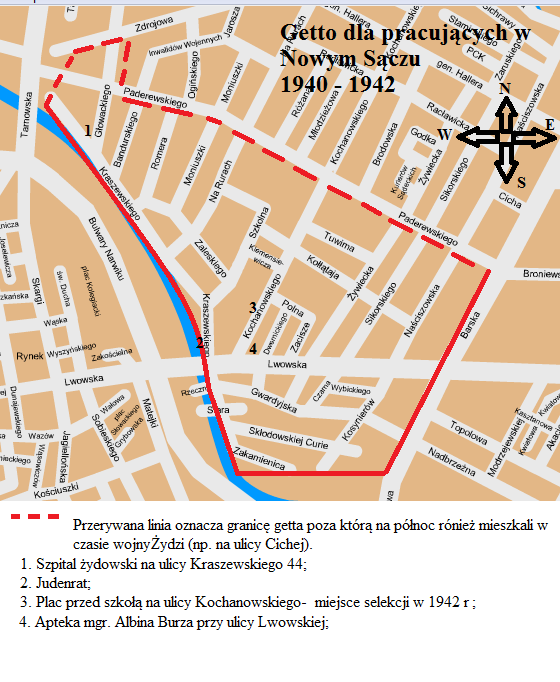

MAP

– – – – The dotted line marks the border of the ghetto, beyond which (to the north) Jews also lived during WWII (e.g. on Cicha Street).

1. The Jewish hospital at 44 Kraszewskiego Street.

2. The Judenrat.

3. The square in front of the school on Kochanowskiego Street – the site of the 1942 selection.

4. Albin Burza’s pharmacy on Lwowska Street.

5. The orphanage.

TABLE 3 – Ghetto in the Kazimierz neighbourhood

The Germans created a closed Jewish quarter between the Market Square and the castle. The exact boundaries of the area, which the population enclosed in it was forbidden to leave, were finally set on 12 August 1940. The punishment for crossing the ghetto boundaries without the required permits was ruthless, including death.

Here, in contrast to the ghetto in the Piekło neighbourhood, Jews deemed unfit for work were placed. The living conditions in this part of the ghetto were incomparably worse than in the part for those working. As a result of new resettlements, crowdedness and the number of residents grew steadily, because Jews from other towns in the Nowy Sącz region, as well as from Krakow and other places, including the regions incorporated into the Reich, were relocated to Nowy Sącz in the spring of 1940. At its peak, the Kazimierz neighbourhood ghetto had up to 18,000 people. Hunger quickly set in and there was a shortage of accommodation.

THE NOWY SĄCZ GHETTO WAS SURROUNDED BY A THREE-METRE-HIGH WALL IN THE SUMMER OF 1941.

While the ghetto was in operation, the Germans organised special actions aimed at humiliating the Jewish population. Among other things, they herded Jews into the Market Square, forcing them to dance on command, walk on all fours and do other physical activities. Witnesses remembered a Jew named Joszua, who was tied to a horse and tortured to death by being dragged along the ground. Eugenia Nowak, who survived the ghetto, recalled that the German torturers burst into the ghetto every few days and murdered people. Shots and screams could be heard every night. As she testified after the war, “There were also scenes when Gestapo men would grab Jewish infants by their feet and smash their heads (…) There were scenes when drunk Gestapo men coming into the ghetto at night ordered people to strip naked and do various circus acts.” The sudden raids did not give the inhabitants a chance to escape. Among others, the Folkmann family of six was murdered. The Germans named Reinhardt, Silling and Johan, who was the head of the prison, particularly stood out in this kind of criminal activity.

At the end of April 1942, the Germans murdered about three hundred Jews in the cemetery, and another hundred ghetto residents in further raids on apartments. Ghetto inhabitants were subjected to humiliation, beating or death on a daily basis at the hands of the Germans, as well as at the hands of the notorious “Jewish police” they had created, whose headquarters were located at the corner of Bożnicza and Piotr Skarga Streets.

TABLE 4 – The symbolism of the memorial

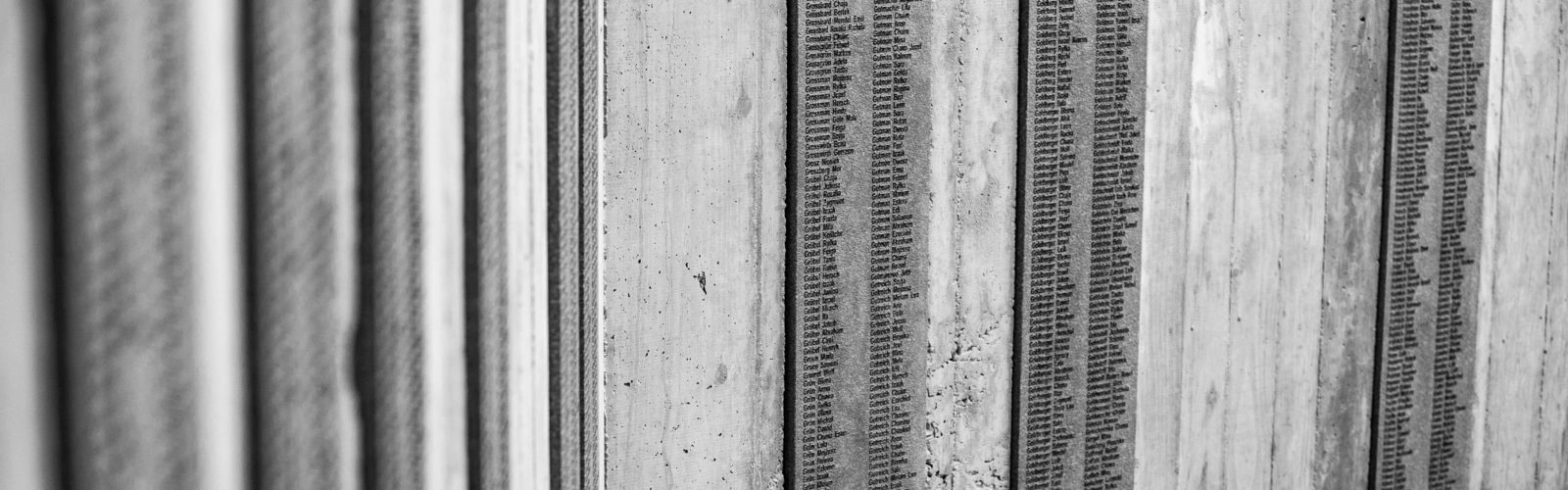

The site was designed by architect Paweł Kurzeja, free of charge. The concept of the memorial has an extremely rich symbolism, allowing each viewer to perceive it differently.

The design of the memorial is reminiscent of that at the former German death camp in Belzec. Similarly, it was made of raw concrete, and its focal point is the niche below street level. Entering the niche, one feels the coldness, darkness and severity of the place. Leaving it, one is supposed to experience a kind of “catharsis”, a cleansing, a reflection on what happened at this place in August 1942. Inside the memorial, almost twelve thousand names of Jewish inhabitants of Nowy Sącz and the region who perished during World War II are inscribed on tablets resembling boards. The whole gives the impression of the names merging into one another. The tablets are pressed into raw concrete, visible between them, which alludes to the cattle cars in which the Jews of Nowy Sącz were transported to Belzec.

The height of the concrete walls also has a symbolic meaning. Standing at the lowest point of the memorial, one can see a wall the height of which, over two metres, is identical to that of the wall surrounding the Nowy Sącz ghetto. Then there is a window on the south-eastern side of the memorial, which refers to several things. Firstly, the only preserved part of the ghetto can be seen through it; all the rest of the ghetto was destroyed when the castle was detonated. The window also alludes to the small windows in the cattle cars.

The symbolism of the site is also visible from above. One can see the broken, incomplete Star of David. The shape also resembles the letter ‘v’ for victory, because the creation of this site represents victory over oblivion, the latter of which the German oppressors in Nowy Sącz wanted to achieve. The gap in the monument is also poignant, and is like a wound cutting through this square.

TABLE 5 – The people of the project

It all started in 2008, when Łukasz Połomski met Jakub Müller. Fascinated by his stories about a world that no longer existed, Łukasz began to delve more and more into Jewish history. In 2009, he met Markus Lustig. It then turned out that Artur Franczak was also interested in this subject. When Jakub Müller died in 2010, they decided to continue his work. On 29 July 2011, Łukasz Połomski founded the „Sądecki Sztetl”, or „Nowy Sącz Shtetl”.

Their work consisted in conducting research which documented, among other things, the Holocaust of the Jewish community. Artur Franczak also engaged in educational activities. In 2013, the two members of the Sądecki Sztetl saw that someone commemorated the old Jewish cemetery by pinning up information sheets there. This is how they met Dariusz Popiela, and the team’s work has further accelerated ever since. The first commemoration the three of them carried out was in memory of Jacob Müller: a plaque commemorating this Guardian of Memory was unveiled in the Jewish cemetery on the third anniversary of his death. In 2014, the Nomina Rosae Foundation became involved in the efforts of Sądecki Sztetl, which made it possible to organise a series of artistic events. Sądecki Sztetl became recognisable not only in Nowy Sącz, but also in the entire region. The first post-war Jewish festivals, and commemorations of Holocaust victims were organised. Dariusz Popiela also set up his own foundation and initiated the “People, Not Numbers” project, but was still active in Nowy Sącz.

The idea of a memorial appeared for the first time in 2013. While he was still alive, Jakub Müller indicated the site where he thought a worthy monument should be created. In 2020, the decision was made to take up this challenge. Once the site had been identified, and the architect Paweł Kurzeja’s concept had been approved, the time came to implement the idea. Many members of Sądecki Sztetl (Aneta Święs, Edyta Danielska, Przemysław Jaskierski) and People, Not Numbers got involved in the project, which was endorsed by the city authorities and descendants of Nowy Sącz Jews, who actively supported all activities.

Part of the project work consisted in compiling a list of victims for the memorial. The list featured the names of Jews born in Nowy Sącz, living in the city before the war, and those who were deported from Nowy Sącz to Belzec. The list also commemorates Jews from the surrounding villages and communities of Korzenna, Łososina Dolna, Chełmiec, Rytro, Łabowa, Podegrodzie, Gródek nad Dunajcem, Kamionka Wielka, Nawojowa. The main basis for compiling the list were documents from Yad Vashem, the Arolsen Archive, the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, the archives of the Institute of National Remembrance (IPN), and Gesher Galicia, as well as lists of those murdered drawn up by their descendants and the Nowy Sącz Landsmanschaft. All this was prepared by Łukasz Połomski. The entire list was later verified by a team of volunteers consisting of Dr Karolina Panz, Sylwia Kosecka, Anna Staszel, Aneta Święs, Beata Szewczyk, Katarzyna Wandas, Zuzanna Leśniak, Inga Marczyńska, Magdalena Staszak, Ewa Teleżyńska, Kaja Andrzejczuk, Mirka Andrzejczuk, Lidia Różacka, Agnieszka Fuczik, Anna Jaskierska, Przemysław Jaskierski, Artur Franczak, Dariusz Popiela, Maciej Batkiewicz, and Wojciech Głowacz. The ceremony was prepared by Kamila Popiela, Dariusz Popiela, Artur Franczak and Łukasz Połomski. The graphic side of the project was supervised by Joanna Kurczap.

The memorial was officially opened on 28 August 2022, the 80th anniversary of the liquidation of the Nowy Sącz Ghetto.

Translated by Adam Musiał